Continuous casting of sheet metal

From DDL Wiki

Continuous casting is a common process for refining many different types of metal such as aluminum, copper and steel. For ease of discussion, this page will only consider continuous casting of sheet steel.

To begin the process, raw materials (called a “charge”) are fed into a large bucket. A typical charge can weigh over 200 tons. The loading can be done using an electromagnet, a crane or even a conveyer belt. The contents of the bucket are dumped into a large furnace where it is melted.

The furnace is heated by arcing electrical current through the metal. The arc travels from an electrode in the roof of the furnace and an anode in the bottom. The electrode is consumed during this process, so it must be continually fed and replaced often. To aid in the melting process, oxygen is also commonly blown into the furnace. A typical melting cycle lasts about an hour, after which the charge has reached temperatures in excess of 2000 degrees.

Once the target temperature is achieved, the molten metal is poured out of the furnace into a ladle. Once the ladle has been filled it moves to similar but less powerful furnace. This furnace is not meant to heat the charge, only to keep it hot while solid alloys are added. Samples are taken to ensure metallurgical specifications have been met. The customer dictates these specifications when the order is placed. Many physical properties of the metal can be affected based on the chemistry of the mixture. For example, steel produced for outdoor applications is commonly high in copper because it increases resistance to oxidation.

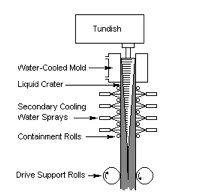

After the metal has been alloyed, the ladle travels to the caster. To begin casting, a large piece of metal called a “dummy bar” is inserted into the bottom of the mold, effectively closing the bottom. The ladle is positioned above an intermediate container called a tundish. Metal flows at a constant rate from the ladle to the tundish and from the tundish into the mold. The walls of the mold are water cooled and a shell of solidified metal contains the remainder of the molten metal. The dummy bar is then extracted from the mold and is closely followed by a strand of metal. After exiting the mold, sprays of water cool the metal to the point at which it becomes completely solid. When the ladle is empty it will be immediately replaced by another with the goal of never interrupting the casting process.

Individual slabs are created by cutting the continuous strand. They can be cut using either a shear or a torch. At this point in the process, the temperature of the slab is not uniform so it travels into a reheat furnace. This furnace is gas fired and very large, so many slabs can remain inside it at any given time.

When the slab has reached uniform temperature, it is fed from the reheat furnace to a rolling mill. The slab is fed through several sets of rollers, each squeezing the slab progressively thinner. As the slab is squeezed thinner, it must speed up to conserve mass flow. Upon exiting the rolling mill, it is immediately coiled and banded. Samples are once again taken to ensure physical specifications have been met. Once all the tests have been performed it is shipped to the customer.

Putting a charge into the furnace creates a fireshow as dust other combustibles are incinerated.

A view inside the furnace. The jets of flames coming from the walls are the locations of the oxygen lances.

This is a fully solidified slab after is exits the caster. The dark spots are oxidation. In the middle you can see the sheer and on the right the entrance to the reheat furnace.

A diagram showing the many of the major components of the caster.